Canva: A Swiss Army Knife for Educators and Content Creators

I was a strict user of the aging MS Publisher, Power Point, and other graphic design tools until I met Canva. I had the basic or free version until I agreed to try the premium…

Elegies of Lost Things

I was a strict user of the aging MS Publisher, Power Point, and other graphic design tools until I met Canva. I had the basic or free version until I agreed to try the premium…

This was the most positive experience. History channel producers are so professional. I never thought I would ever be on the History channel, much less on this excellent show. I am surprised at the interest…

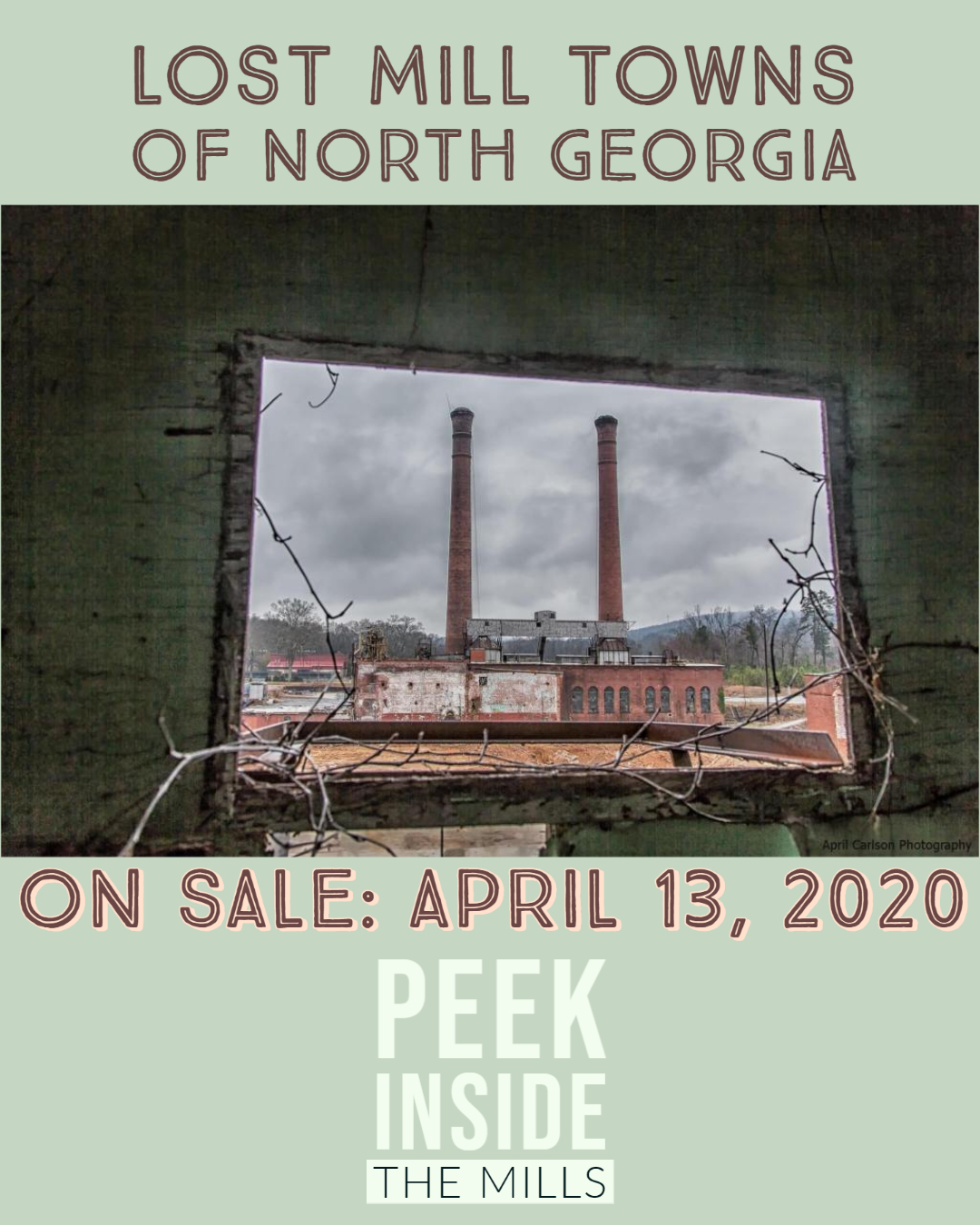

Lost Mill Towns of North Georgia is my favorite. My third book in my lost North Georgia series got lost in Covid-19. I wanted to focus on some things in that book and include more…

Not knowing your history leaves you rootless. Jane Blasio dug into her hidden history, found her roots, and is now planted. Jane shares her journey in but is now rooted. Jane writes her story in Taken at Birth: Stolen Babies, Hidden Lies, and My Journey to Find Home. She worked with TLC as an investigator on the TLC Docu-Series, Taken at Birth. The series was interesting, but I wanted to know more about Jane. Her book fills in the blanks but leaves you wanting a little more. However, that is the nature of Jane’s story.…

While writing Lost Towns of North Georgia and Underwater Ghost Towns of North Georgia, I came across a late 1800 Atlanta newspaper article about sightings of phantom soldiers on trains going through Allatoona Pass. I…

I hear them. And I want you to hear them too. We ignore them or just half listen to their stories. …

When the bustle of a city slows, towns dissolve into abandoned buildings or return to woods and crumble into the North Georgia clay. The remains of many towns dot the landscape—pockets of life that were…