Canva: A Swiss Army Knife for Educators and Content Creators

I was a strict user of the aging MS Publisher, Power Point, and other graphic design tools until I met Canva. I had the basic or free version until I agreed to try the premium…

Good old writing advice.

I was a strict user of the aging MS Publisher, Power Point, and other graphic design tools until I met Canva. I had the basic or free version until I agreed to try the premium…

This was the most positive experience. History channel producers are so professional. I never thought I would ever be on the History channel, much less on this excellent show. I am surprised at the interest…

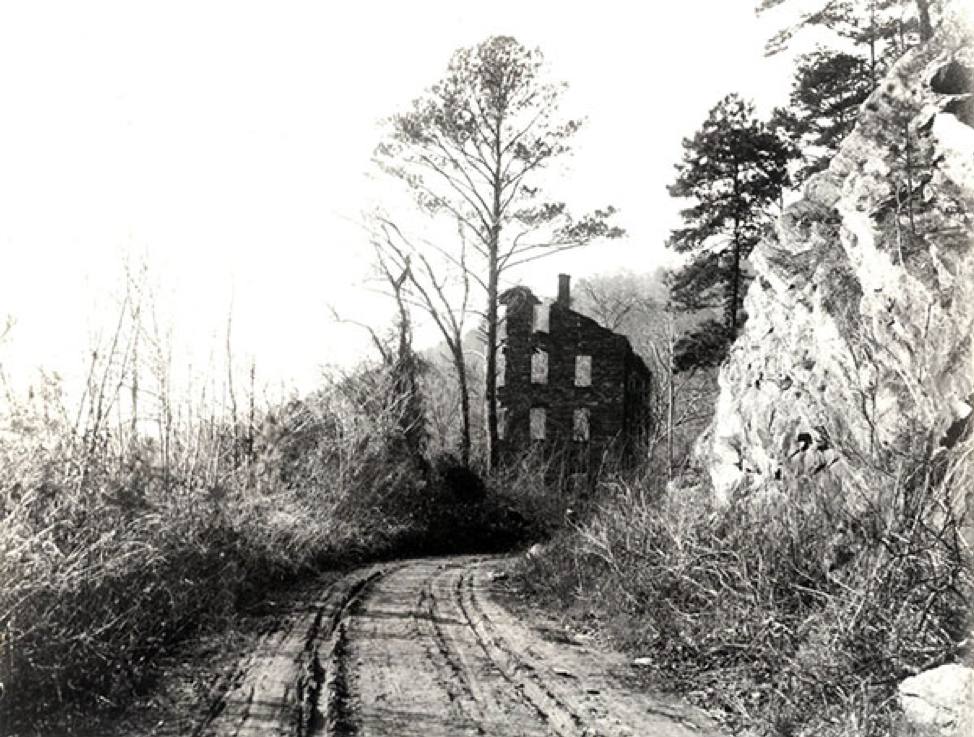

Lost Mill Towns of North Georgia is my favorite. My third book in my lost North Georgia series got lost in Covid-19. I wanted to focus on some things in that book and include more…

Rising from the red clay-stained waters of Lake Allatoona, Glen Holly teases a few times a year. When the water retreats, a home place appears. War, fire, nature and water have finished their work to dismantle…

There are some interesting thoughts on my “old” blog about writing: https://lisamoserrussell.wordpress.com/ Do you want an autographed copy of my book, Lost Towns of North Georgia?[wpecpp name=”Autographed copy, “Lost Towns of North…

“Scattered words and phrases hide your word design; it may be time for a writing makeover. Rewriting eLearning content starts by using your word-processing tools to spot wordiness. With practice, concise writing will become your…