What’s so Special about Chicopee?

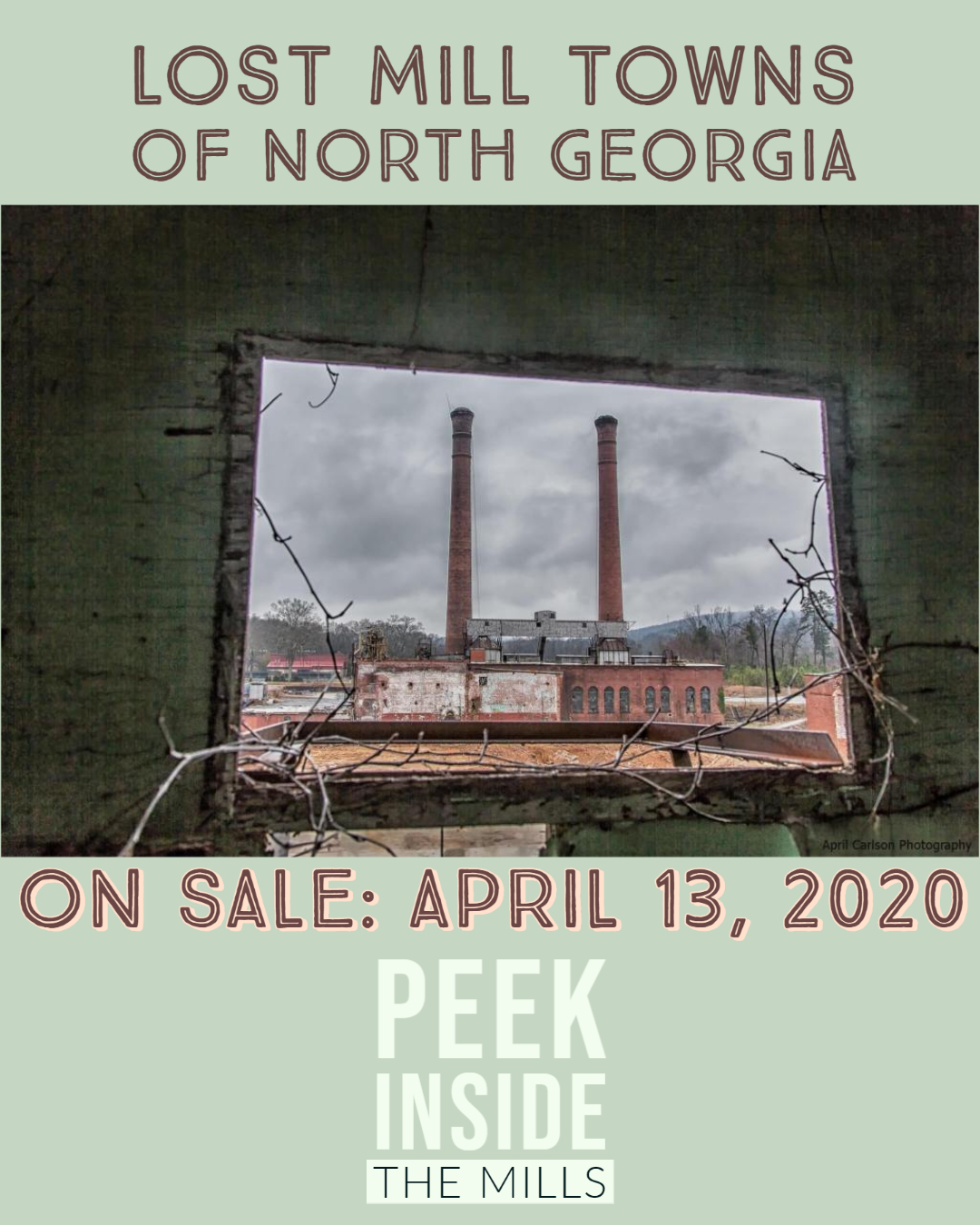

Lost Mill Towns of North Georgia is my favorite. My third book in my lost North Georgia series got lost in Covid-19. I wanted to focus on some things in that book and include more…

Lost Mill Towns of North Georgia is my favorite. My third book in my lost North Georgia series got lost in Covid-19. I wanted to focus on some things in that book and include more…

I hear them. And I want you to hear them too. We ignore them or just half listen to their stories. …

Cassville or the story of Cassville has chased me for years. I went to Cassville Baptist just before 2000. We left just after 9/11. When I left the church, I carried the stories with me and…